Rules of the game

BLUE means don’t-move words.

ORANGE means self-move words.

PURPLE means other-move words.

YELLOW means self-move words that lost their movements.

PINK means other-move words that lost their movements.

Every word links to a jisho.org page. Just click the word!

After this lesson, particles won’t be much of a secret to you anymore. These particles are a very important part of japanese grammar. But first, let’s introduce you a concept.

Move-word group

If it was english, this would have been named “Verbal group”. But that also works for all the move words. Simply put, this is the group of words that define the movement.

We already saw the “don’t-move words attached to move words to make a move word” : 告白 : A confession. する : do. 告白する : Do-confession ==> To confess. This is indeed one part of the move-word group. Note that it also exists for move words that have lost their movement and are attached with a move word. 受ける : To receive. 受け : a reception. 入れる : To put in. 受け入れる : To put in-Reception ==> to take in.

A very important thing to consider is that 勉強する and 勉強をする are grammatically very different. 勉強する is a move-word group, and can take an object : 数学を勉強する : To study mathematics. This is not possible with 勉強をする : “To DO what? Studies”, since, as you can see, only する here belongs the move-word group, and 勉強 is the object. You cannot have two objects for a move word. Only 1 subject and 1 object for a move word.

To add to this, で and に particles are the superheroes that also help forming the move-word group. Put in another way, they modify movement. Japanese does not work with Indirect Objects and all that stuff. Powerful right?

Before explaining how they do this, I have to do what I love to do : clear up lies.

The て form of verbs

For those who made some japanese lessons before, are you stressed? You worked so hard to understand these, and I am about to tell you this was all a lie?

Yes, it’s a “convenient” lie from japanese textbooks. These books prone using japanese, not understanding it. But the で particles’ usages are pretty wide, so they separated them into で particles and て form of move-words. But this is the same thing : The で particle.

食べに行く ; 食べていく. This is the same construction, the で particle is just hidden. The most outrageous thing here is that both of these sentences can be translated as “Going to eat”, in different contexts. As you can see, you can both construct these using the い conjugation that makes verbs lose their movement, い for verbs and く for adjectives. We also see that に doesn’t change the look of the verb, but で does. So how to do it with で for verbs?

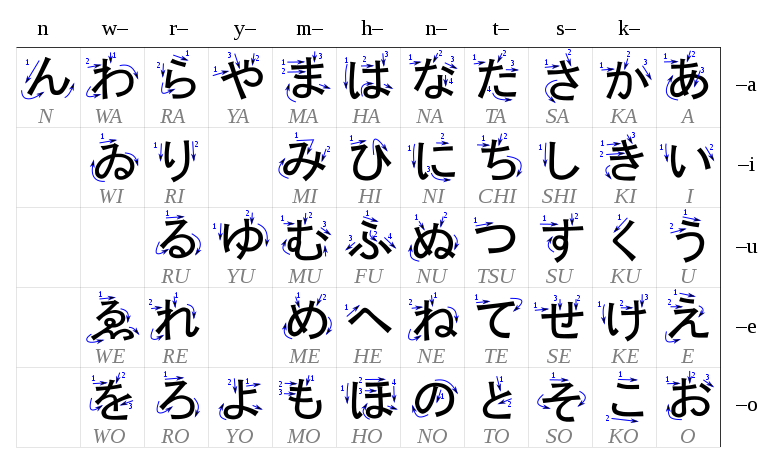

… Depending on the last sound of the verb! You don’t really have to learn all て form by heart, you can simply get them on the way while you read. But I still tell you how to get them here :

い (ゐ) : 買い ==> 買って ; き : 書き ==> 書いて ; し : 返し ==> 返して ;

ち : 勝ち ==> 勝って ; に : 死に ==> 死んで ; ひ : doesn’t exist

み : 噛み ==> 噛んで ; り : 狩り ==> 狩って ; び : 転び : 転んで

し has no surprise. き is the phenomenon explained last lesson about adjectives (素晴らしき日々 ==> 素晴らしい). み, に and び are “mouth closed” (explosive sounds), then in becomes んで. い used to be ゐ so it became って instead of て. ち and り end with the tongue on the palate, so it becomes って.

As for adjectives? Well, you also remove their movement with the い conjugation, that means from い to く for adjectives, and you add て for the て form. 面白くて.

And for the に particle on adjectives? It’s not used much anymore, but it was used in ancient japanese, it changed from 面白くに to 面白く simply. 怪しく笑う : To laugh weirdly.

Everything is super-duper logical, you see? From now on, I’ll call a verb which has lost its movement and a で particle (増して) a て form, according what books do. So now, what do these two particles do exactly?

A problem of range

(My passion for philosophy will show in this part. Don’t blame yourself if you don’t get everything)

Let’s take a simple example. We take the word “to go”. Its definition :

As we can see here, “one place to another” is INSIDE the verb itself. What if we want to “Go TO PARIS”? Simply, we reduce the possibility of the verb, we cut it with the tool “to Paris”. We have removed a part of the verb itself. But what about saying “Go ALONE”? There, we have taken another concept and ADDED it to the original word. It’s not there in the word in the first place.

But what about “Go Tomorrow” then? Well, while it’s technically not included in the definition of the verb anymore, you are still reducing possibilities. It could have been anytime! And then, what to say about “Go with a bicycle”? What we’re doing here is not exactly a choice. We are not really “removing freedom” from the verb, rather, we “add a way for the verb to act”. Using a bicycle adds new possibilities to the verb.

You know what? In theory, this is exactly what に and で do! に removes possibilities, removes freedom, and, in opposition, で adds possibilities, adds new ways for the move-words to act.

But… How do we reduce the possibilities? It’s a little scientific.

- When you have one result, a single possibility, and you want to know how it was caused, you look at the past, to see all the possibilities, conditions met.

- When you have one situation, with thousands of possibilities, and you want to know what it leads to, you turn yourself to the future, to see the result.

To be fair, possibilities of verbs sound a bit like fate. Fate is unique, but, in the past, the possibilities are infinite! In another explanation, let me show a little situation. Take a funnel, the Funnel of Possibilities. You want to have a bigger circle? Make it bigger with a で. A little smaller? Cut it lower with a に!

These two particles are probably the most used in all of japanese. And for a reason, as you can see, they are very useful and flexible! But now, you might ask for some real examples to clarify all of it.

に and で examples

Here, we have どうするのか? which roughly means “what are you going to do?”. 訊き (訊いて) is affixed to it with the particle で, adding a new meaning to the move-word する. ことを訊いてする. Here, we guess 訊いて ADDS “the current situation when the する move word begins”. We can translate “What are you going to do after asking this thing?”

Generally, when a move word has a て form of a verb linked to it, and there are words in between, like the last example, this is a succession of actions. I will talk about usages more precisely in patchwork lessons.

Now, a more complete one.

うん。前に独房エリアを探索している時に見つけて、お父さんに渡したんだ

Let’s analyse 前に独房エリアを 探索する : “Explore the isolation area” + the verb has 前に linked to it, LIMITING the time when the action occured to “a while before”, when it could have been anytime.

している is literally “to exist” (いる) + て of “to do”. It means “be doing” here, I’ll explain this more in details in a later lesson and in patchworks.

ときに見つけて, we can guess easily it’s “find” + limited to a “time” ==> find at this time.

And finally, we have 見つけて、お父さんに渡した (The た is commonly the “past”, I will explain to you next lesson). “To hand over ” + に of “Father” and て of “Find”. We could have given it to anyone, we reduce it to “Father”, so we have に. And, just like the last て, we add the concept of “situation when it began” with the で to the move-word. We get for this part : Hand it over to father after I find.

The whole translation that we well deserved is “Yes. I was searching the isolation area a while before, then I found it, then I gave it to father”. It wasn’t too bad, see?

A quick sum up (I know you need it)

Cut with a knife? You take a knife, then you cut. You got new possibilities with a knife for the verb. Particle で

Eat together? You are together, then you eat. Together adds possibilities to the verb eat. Particle で

Go somewhere? You start going, and then you get to the place. You could have gone anywhere else, you removed possibilities. Particle に.

Do something somewhere? You are somewhere, then you start doing stuff. You add possibility to the verb of action (verb doesn’t act spacially). Particle で

Choose the best in a set? You take the set, then you chose the best. The two words work together. You add possibilities to the verb : The one chosen isn’t necessarily the best overall. Particle で.

You receive from someone? You could have received it from anyone, saying from who removes the doubt. Particle に.

It know it still sounds abstract and that you feel like you need to think to get them right. But you know what?

It’s okay.

You’re obviously not going to understand everything from the beginning in this lesson, and I’m conscious of it. I also mistake に and で from time to time, and honestly, it’s okay. If you understood that “に and で particles modify the move word”, that’s honestly more than enough. Besides, you’ll be provided with more examples and references in the next lessons, and you’ll get them anyways with experience, so don’t worry. The next 2 lessons will be very useful to your immersion, you will be able to get by quite well in your japanese immersion after them, and from now on, the difficulty is going down.

You made the hardest part, but it’s not a reason to stop now! Onto the next lesson!